The Art Of The Trade

Active investors know trading isn’t just crunching numbers, it’s performance art with a touch of masochism. It takes skill, discipline, and the mental fortitude of a monk watching a tech stock crash. Markets don’t move on logic alone, they dance to the erratic rhythm of human emotion, hype, and herd mentality. Mastering this chaos? It’s all about timing, strategy, and executing your plan before your nerves execute you.

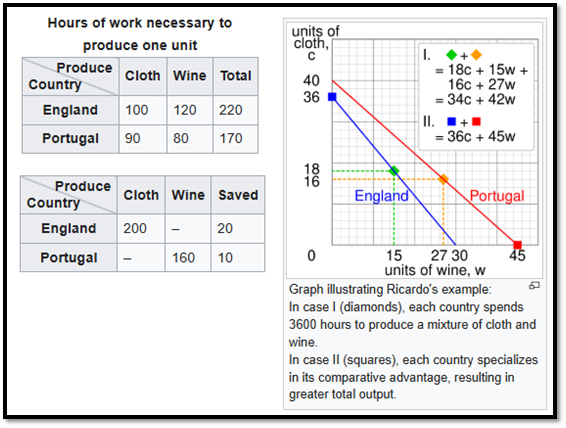

International trade isn’t a chess match, it’s poker with tariffs, bluffing, and the occasional diplomatic side-eye. Countries trade not out of love, but necessity (plus a dash of geopolitical showmanship). The winners? Those who read the room, dodge economic landmines, and fake confidence at global summits. In theory, it all rests on Ricardo’s 19th-century gem: comparative advantage. Do what you’re least bad at, trade the rest, and somehow everyone wins. Even the economic underachiever gets a trophy, as long as they specialize. It’s efficient, elegant, and works great… until someone flips the trade table.

David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage worked well under a gold standard, where trade imbalances were naturally corrected by flows of gold that constrained monetary expansion. However, the modern global trade system has drifted far from that model. Today, trade often involves one side exporting real goods and the other paying with fiat currency, especially U.S. dollars, which are accepted not because it represents an exchange of equal value, but because it was need to buy strategic resources like oil until USD assets were weaponized in 2022.

This imbalance is amplified by the United States' unique position of "imperial privilege," allowing it to run chronic trade deficits without facing the usual consequences. Instead of paying in kind, the U.S. issues dollar-denominated assets, essentially IOUs, which other countries accept and reinvest in U.S. financial markets. Over time, this dynamic has hollowed out American manufacturing, encouraging an economy focused more on consumption and financial services than on production. Meanwhile, other countries participate in the system by manipulating currencies, offering industrial subsidies, or exploiting tax loopholes through offshore hubs like Ireland. The result is a global economy where trade flows are less about comparative efficiency and more about who can best game the system. Instead of fostering mutual prosperity through productive exchange, the ‘pre-Liberation Day’ trade system rewarded financial engineering and leads to long-term structural imbalances.

https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/PP-1-31-12.pdf

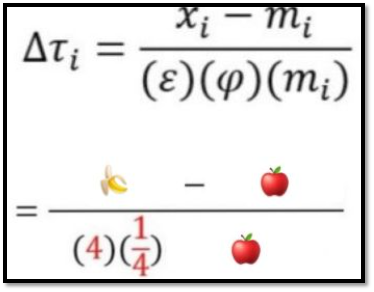

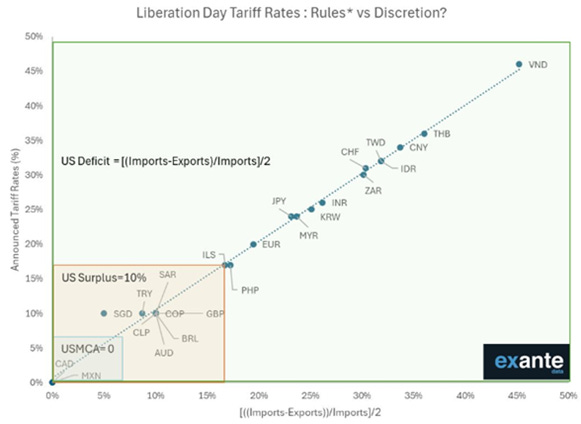

Fast forward to the so-called U.S. Liberation Day on April 2nd, 2025: the ‘Disruptor-in-Chief’ unveiled what will go down in financial history books as Reciprocal Tariffs, a policy wrapped in the illusion of scientific rigor, supposedly based on U.S. import and export figures.

To simplify: if we swap his formula for 🍎 and 🍌, it becomes clear why penguins 🐧 in Antarctica are somehow being taxed. Why is this even considered reciprocal tariff calculation? This formula is clearly just a fancy way of stating: U.S. trade deficit / imports.

🍌 = exports, 🍎 = Imports.

Trump likely hopes to fix trade imbalances and U.S. deficits with tariffs. Admirable in theory… but impossible in practice, at least as long as the U.S. dollar remains the world’s dominant trading and reserve currency. Someone really should brief the administration on the Triffin Paradox: any country issuing the global reserve currency must run a deficit. That’s the price of power. The world needs more dollars than the U.S. can earn from exports alone, so the U.S. prints them, and voilà, its biggest export isn’t tech or oil, but money itself.

Tariffs might feel like action, but if pushed too far, they’ll end up taxing the U.S. out of reserve currency status. Classic case of “be careful what you wish for”, you just might get it.

Take China, for example: it runs a surplus with the U.S., but only because it imports raw materials to make the stuff Americans buy. A retaliatory tariff doesn’t mean China’s playing dirty, it just has a more efficient way of producing the Americans didn’t want to produce anymore. That’s the trade deal. The U.S. needed China’s low-cost goods, and China needed American consumers until it develops its own domestic consumer market. In return, China bought U.S. debt, once considered a safe bet but not anymore. As trust erodes, so do trade ties, and America’s partners are quietly heading for the exit.

Anyone with a sliver of common sense, and not currently starring in a trade war fantasy, knows global trade isn’t a perfectly balanced seesaw. Poorer countries don’t have the cash to splurge on U.S. goods. Their wages are a fraction of the U.S. minimum, which makes their products cheaper by default. No, Cambodia isn’t dreaming of Detroit sedans, and their factories won’t pack up and head to Ohio to dodge a 49% tariff. They’ll just find new customers who don’t throw tantrums over trade deficits. Imbalances aren’t a bug; they’re a feature of global trade. Treasury Secretary Bessent’s “Let them eat flat screens” line missed the point entirely. Yes, Americans got cheap TVs, but here’s the real kicker: these tariffs are scaring off investors. Because, shockingly, major companies don’t want to play economic isolationist cosplay.

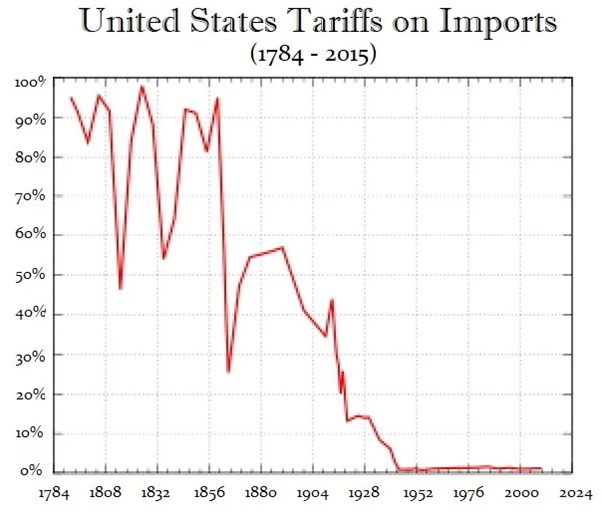

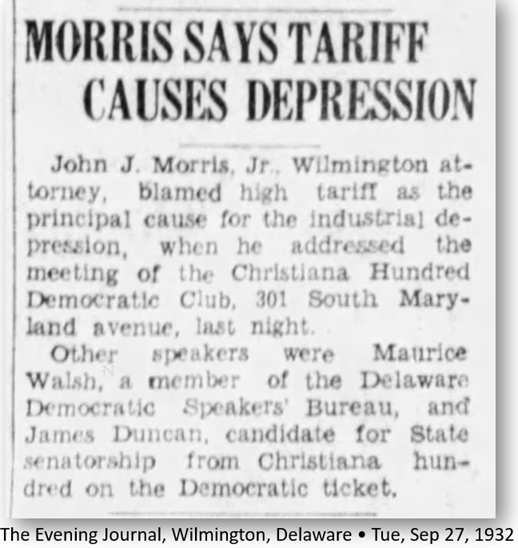

While the financial media loves to chant that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff caused the Great Depression, that’s more fairy tale than fact. Yes, it made a convenient villain in Econ 101, but a look at the chart of U.S. tariffs since 1784: spoiler alert, Smoot-Hawley in 1930 targeted agriculture, not industry, and it wasn't exactly the first tariff rodeo. What the media, and Galbraith in The Great Crash, conveniently left out? The global sovereign defaults of 1931. But hey, why blame governments when you can point fingers at evil corporations instead? After all, Galbraith was a socialist, so businesses who create real wealth had to be the scapegoat. Sure, some argue Smoot-Hawley contributed to the Depression. That’s the diplomatic way of saying “it didn’t help.” But saying it was the cause while ignoring the avalanche of sovereign debt defaults? That’s just bad history. Smoot-Hawley didn’t even become law until June 17, 1930, by then, the stock market had already plunged from its September 1929 peak. Yes, traders may have anticipated it, as Cato’s Alan Reynolds pointed out. But does that mean the market would’ve kept soaring “but for” the tariff talk? Come on. As if a single bill derailed an entire global economy already drowning in debt and denial.

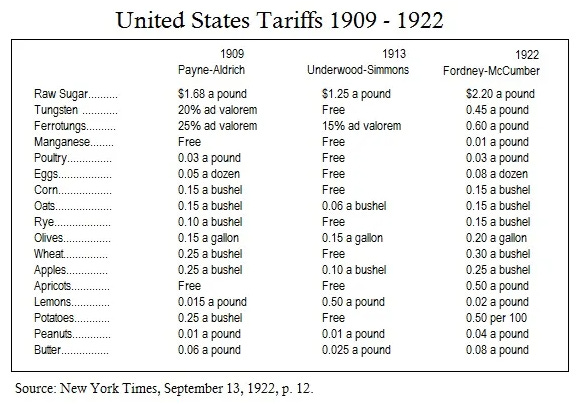

In a nutshell, the idea that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff caused the Great Depression while ignoring the European Sovereign Debt Crisis is a weak argument. Tariffs like the 1921 Emergency Tariff and Fordney-McCumber Tariff were already in place, pushed by nationalism and protectionism after World War I. These measures, aimed at protecting U.S. prosperity, predate Smoot-Hawley and were part of a broader trend of isolationism.

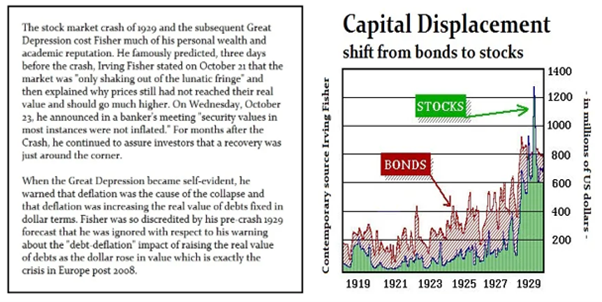

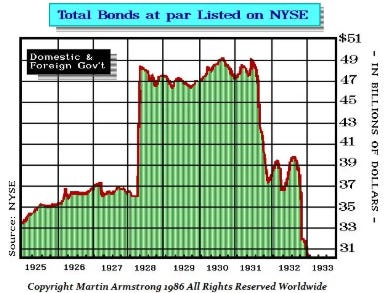

The real problem wasn’t tariffs, it was DEBT. From 1927 to 1929, as signs of a European debt crisis emerged, investors shifted from bonds to equities, causing a ‘Phase Transition’ in markets, where capital concentrated in specific sectors and countries, leading to massive price increases. This wasn’t just inflation; it was a fundamental shift in capital.

Irving Fisher, a prominent economist, lost credibility when he claimed the market had reached a new plateau and wouldn’t crash. He misunderstood the shift from bonds to equities, which can be termed a "Phase Transition." The shift from bonds to equities can lead to a new plateau, provided it occurs gradually as a trend. When it erupts in the short term and causes a doubling of prices, it’s a warning sign that we’re dealing with a bubble, not a broad shift in the investment trend.

To understand the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs, often blamed for contributing to the Great Depression, we must consider the broader global and domestic economic context. In 1927, there wasn't just a secret meeting among central banks to lower U.S. interest rates to deflect capital flows back to Europe, but also the League of Nations’ World Economic Conference in Geneva, where it was officially decided that tariffs should be reduced. Despite this, France, resentful of Germany, broke ranks and enacted new tariffs in 1928, targeting Germany. These tariffs were designed to block Germany from making reparation payments imposed after World War I. The German people, punished for the actions of their political leaders, faced harsh economic conditions. This resentment contributed to the rise of Hitler, as the French failed to differentiate between the German government and its people.

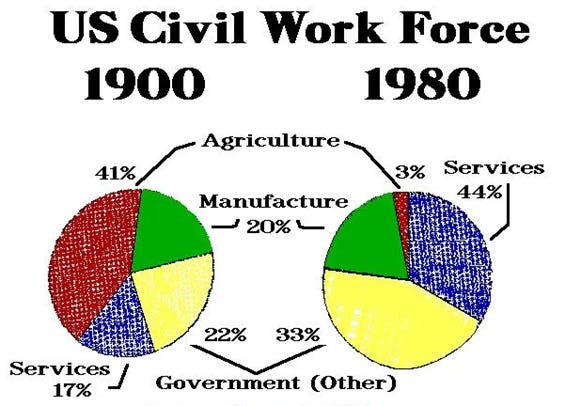

On the other side of the pond, the economic shift in the early 20th century, driven by the advent of electricity and the combustion engine, transformed the U.S. economy. In 1900, around 40% of the workforce was in agriculture, but by the late 1920s, productivity soared due to electrification and agricultural innovations like tractors replacing horses. This freed up significant land previously used for feeding animals, increasing food production and leading to overproduction and underconsumption. Senator Reed Smoot, a Republican from Utah, and Congressman Willis C. Hawley, a Republican from Oregon, were responding to demands from farmers, particularly in non-industrial states, for high tariffs to protect them from falling prices. However, the issue wasn’t imports, it was overproduction. Smoot-Hawley aimed to shield farmers from this challenge, similar to how the Silver Democrats had supported miners in the late 19th century.

Meanwhile, the U.S. was still running a trade surplus due to rising manufactured exports after World War I, while food exports declined as Europe rebuilt its agricultural sector. The farmers' struggles were more about this shift in agricultural dynamics than concerns over foreign competition. Smoot's support for the tariff increase in 1929, which became the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, reflected his belief that the world was paying for the destruction caused by the war and the failure to adjust purchasing power to new industrial realities. However, he overlooked the profound economic changes brought on by technological advancements like electricity and the combustion engine.

In the 1928 Presidential election, Herbert Hoover promised to support farmers by increasing tariffs on agricultural goods. After winning, Hoover asked Congress to raise tariffs on agriculture while lowering them on industrial products, aiming for a balance to satisfy trading partners. In May 1929, the House passed a version of the tariff bill, focusing on agricultural goods. Critics of the Smoot-Hawley Act argue that the market crash of 1929 was triggered by the bill's passage on May 28th. However, this claim is inaccurate. The bill passed on May 28th, which coincided with the market's low point, but it wasn’t the cause of the downturn. The real catalyst was the British elections on May 30th, which resulted in a hung Parliament, seen as a political crisis. The very next day, Ford Motor Company signed a significant contract with the Soviet Union, further distancing the market response from the tariff bill. The market reaction was more influenced by these events than by the tariff debate, and there was a clear distinction between the impacts of agricultural versus industrial imports.

Dow Jones Industrial Average between December 1927 and December 1932.

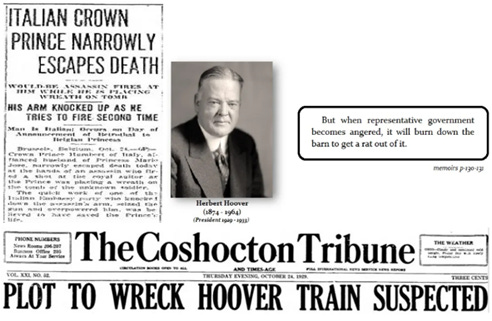

Those who blame tariffs for the 1929 crash point to October 23rd, when it seemed tariffs would be broader than expected. However, no headlines support this narrative. On that day, bankers tried to stabilize the market, but their failure caused a collapse in confidence. Additionally, an assassination attempt on the Italian Crown Prince heightened American concerns about Europe's instability. The tariff argument was pushed by Democrats, similar to their later critiques of Reagan’s "trickle-down" economics. Some senators, including William Henry King, called for investigations into the Federal Reserve and proposed tax hikes on stock sales. Senator Carter Glass pushed for a 5% excise tax on stocks held for less than 60 days, which he tried to attach to the tariff bill. Focusing on tariffs as the cause of the crash is misguided—what truly concerned investors was the proposed tax on stock investments, not the tariffs themselves.

The US Senate debated the tariff bill until March 1930, with Senators voting based on their states' interests. The bill passed with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats from farming states. The conference committee then aligned the Senate and House versions, moving to the higher House tariffs. The final bill passed the House 222-153, supported by 208 Republicans and 14 Democrats, primarily influenced by farmers. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, signed into law on June 17, 1930, implemented protectionist policies. However, when the law was enacted, no significant headlines predicted an economic collapse. Bankers again attempted to stabilize the market, but no commentary blamed the tariffs for the market's decline. Democrats used the tariff as a political attack against Republicans, but the true cause of the crash was the default on sovereign debt sold by investment banks to the public, wiping out savings and causing widespread bank defaults. Spending cuts, particularly in the military, and the tariff issue further fueled political debates, with many in Congress critical of European demands for free access to U.S. markets while blocking theirs. The tariff debate stemmed from agricultural overproduction during the transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy, which politicians struggled to grasp. In 1931, bankers' failed attempts to stabilize the market led to a loss of confidence in both the government and the financial system. Investors were scrutinized, and the Senate held hearings on stock market practices. On March 2, 1932, the Senate authorized an investigation into the buying, selling, and lending of stocks, but the committee made little progress, as banking executives denied requests for documents and witnesses evaded questions.

The same tired playbook was used in 1932, blame tariffs, blame Hoover, and hand FDR the keys to the White House. It was a political con job then, just as it is now. The idea that tariffs caused the Great Depression is a fabrication, peddled by Democrats in 1932 to win an election and now revived in a desperate attempt to impose more malthusian keynesian policies. The media is running the same script: crash the market, blame the outsider, and protect the gravy train.

Never mind that tariffs were being raised globally well before the 1929 crash; 33 major hikes between 1925 and 1929, from Europe to Latin America to Asia. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand got in on it too. Somehow, all that vanished from the history books, along with the 1931 wave of sovereign defaults that actually shattered confidence and wiped out savings. But sure, let’s keep pretending a tariff on sugar and shoes brought down the world economy.

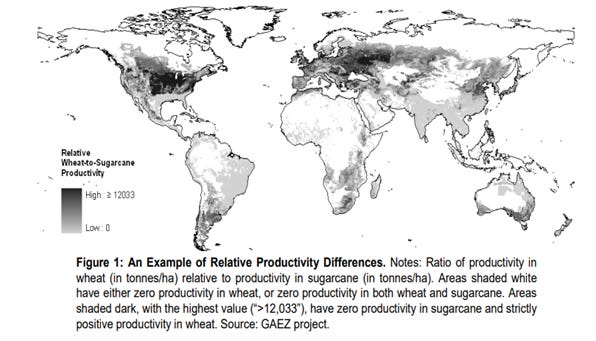

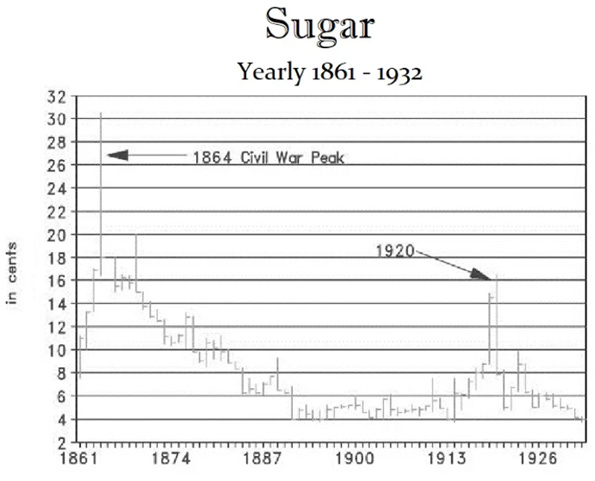

In summary, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 wasn’t the spark that lit the protectionist fire, it was a reaction to the one already burning. The real trade war started before 1929, when Europe, fresh from the wreckage of World War I, tried to claw back its pre-war economic dominance. Capital and production had fled to the U.S. and Latin America during the war, and Europe wasn’t pleased. Take sugar, for example. European production collapsed during the war and shifted to Java, Cuba, and South America. Prices spiked in 1919/1920. But after the war, Europe slapped on high tariffs to push back against these new competitors. The result? Sugar production in Europe not only returned but exceeded pre-war levels by 1927–1928. They pulled the same stunt with cotton and wheat, tariffs that led to overproduction and the loss of export markets. This was the true face of the protectionist wave. But instead of acknowledging that Europe kicked off the trade war to protect its own industries, history pins it all on Smoot-Hawley, because, of course, it makes for a cleaner, more convenient scapegoat.

Outside the U.S., the real shock to the global economy came not from tariffs but from cascading debt defaults. On May 11, 1931, Austria’s largest bank, Creditanstalt, collapsed—triggering a full-blown currency crisis as panicked investors pulled funds from Austrian banks and moved them abroad. Meanwhile, Germany was slipping into political chaos. Just days earlier, on May 8, Hitler had slipped past a legal challenge by Hans Litten, who had tried to hold him accountable for SA violence. Litten would later be arrested after the Reichstag fire and spend years tortured in Nazi camps before taking his own life. His story is haunting—and a grim reminder of what the world was really confronting. To say that tariffs caused the Great Depression? That’s the kind of simplistic scapegoating that made for great Democratic campaign fodder in 1932, but it doesn’t hold up. The real destruction came from the collapse of Sovereign Debt, bonds sold in small denominations to everyday people who thought they were playing it safe. They avoided stocks, only to lose everything when governments defaulted. Unlike stocks, which eventually recovered, these bonds went to zero and stayed there. Even U.S. municipalities like Detroit stopped paying—Detroit paused payments in 1937 and didn’t resume until 1963, just so they could technically say they never defaulted. While the Dow fell 89%, bonds fell 100%, and never came back. But sure, let’s keep blaming tariffs and believe that government debt is a safe haven.

A look at the 1980s, Reagan’s America, the trade deficit was rising, but the economy was booming, go figure. Volcker’s sky-high interest rates didn’t just crush inflation, they also pulled in foreign capital like moths to a flame. The dollar skyrocketed, even sending the British pound scrambling to keep up in 1985. Meanwhile, interest payments on the national debt, totally unrelated to goods or services, were flowing out of the U.S., showing up in the current account.

Dow Jones Index (blue line); FED Fund Rate (red line) between December 1970 and December 1984.

Once upon a time, in a slightly more united States of America, tariffs weren’t just a red-versus-blue shouting match. In fact, long before Trump turned trade wars into reality TV, none other than Nancy Pelosi, yes, that Nancy, was waving the anti-China tariff flag like a proud protectionist.

Back in 1996, Pelosi stood on the House floor decrying the “cruel hoax” of U.S.-China trade. With a passion usually reserved for insider stock tips, she warned of lost jobs, unfair tariffs, and a $34 billion trade deficit ballooning faster than a congressional budget. China, she argued, was eating our lunch, while we politely footed the bill. Her solution? Tariffs. Lots of them. Reciprocal ones. The U.S. was charging 2%; China was slapping us with 35%. Pelosi was outraged. She even brought charts. You know it’s serious when the PowerPoint comes out. Fast-forward to 2025, and suddenly tariffs are “reckless,” “chaotic,” and “the largest tax hike on Americans in history”, but only because the guy proposing them now is named Trump, not Clinton. What changed? Not China. Not the trade deficit. Just the face on the policy. Pelosi’s pirouette is a masterclass in political flexibility, yoga instructors could only dream of that kind of bend.

Turns out, when it comes to tariffs, it’s not about jobs, deficits, or even China—it’s about who’s in the Oval Office. And as always, consistency in politics is about as common as a balanced budget.

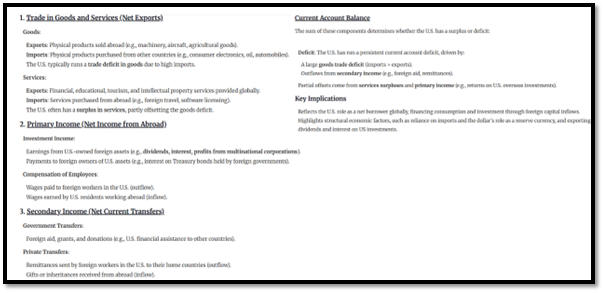

Most people, and let’s be honest, most politicians can not tell the difference between the current account and the capital account if their next campaign donation depended on it.

Here’s the deal: the U.S. runs a trade deficit, and everyone freaks out like it’s a sign of economic doom. But guess what? That’s only half the story. The capital account is the other half, and it’s flushed with foreign money flowing into the U.S. to buy everything from Treasuries and stocks to real estate and tech startups. You sell Apple shares to a Swiss pension fund? Boom, that’s a capital inflow. US company repatriating overseas profits? More dollars in. Now, the current account isn’t just goods and services. It includes income flows, dividends, interest, corporate profits, sent to and from foreign investors. So when the US government sells Treasuries to China, and pay them interest on their $1.1 trillion stash, that adds to the current account deficit. At $1 trillion in total US interest payments, that’s $100 billion in transfers to Beijing alone. But let’s not pretend tariffs will magically fix that.

In fact, tariffs might push foreign investors to sell U.S. assets and take their capital home, shrinking the capital account surplus, and yes, reducing the current account deficit. Not because the ‘Manipulator In Chief’ won the trade war", but because he scared off the capital flows. So next time someone yells “Trade Deficit!” like it’s the end of days, ask them if they’ve ever heard of the balance of payments. Odds are, they haven’t, and they probably sit on a subcommittee.

Even inside the U.S., companies are packing their bags, not for China, but for Texas. Or Florida. Or any state where taxes don’t eat your margins alive. Take Michigan, for example. Sure, they replaced the dreaded Michigan Business Tax in 2011 with a more "friendly" 6% corporate tax rate, but add Detroit’s 2% city tax and you're quickly staring down 8% before Uncle Sam shows up with his federal cut. That’s a pretty tough sell when states like Wyoming or South Dakota are out there whispering sweet nothings like “no corporate income tax.” Now zoom out: U.S. manufacturers didn’t just vanish overseas, they were pushed. Local and state income taxes piled onto federal taxes like an IRS sandwich. And let’s not forget the cherry on top: a Supreme Court decision that blessed worldwide taxation on American citizens and businesses. So yes, the U.S. is basically the only country that taxes you no matter where you go, like the clingiest ex in history.

Keynesians love to paint corporations as villains who offshored for cheaper labor. But in reality, it’s not about paying $10 instead of $20 an hour, it’s about paying five figures to accountants, lawyers, and compliance teams just to survive the U.S. tax maze. And if the IRS sniffs even a whiff of "contractor" vs "employee" mislabeling? Say hello to an audit, and goodbye to $25,000 in legal and accounting fees even if you win. It's not greed. It's tax survival.

Tax rate per US states.

While tariffs aren’t the root of a depression, despite what political mythology keeps recycling, the costs still land squarely on the backs of consumers and entrepreneurs. And now, courtesy of the 47th president, we’re getting a fresh round of economic self-harm wrapped in patriotic rhetoric. Call it what you like, but a tariff is just a tax in disguise, no matter how skillfully it's sold as a blow against foreign adversaries.

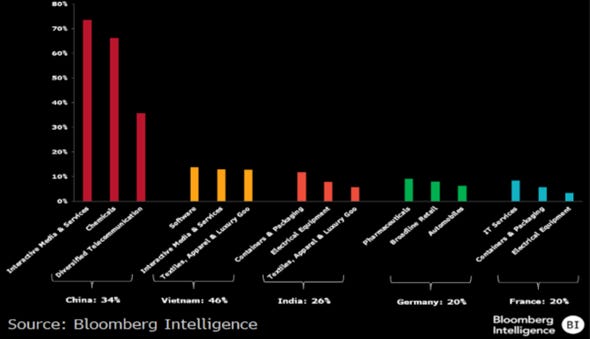

‘Liberation Day’ tariffs are poised to hit tech, media, and telecom (TMT) the hardest. Communications segments like interactive media and diversified telecoms, already highly exposed to China, could face brutal extra duty. Chemicals, too, are in the crosshairs. Meanwhile, textiles, dependent on Vietnam and India, are looking at penalising levies. In short: this isn’t a trade war. It’s a silent tax hike dressed up as economic nationalism.

Read more and discover how to trade it here: https://themacrobutler.substack.com/p/the-art-of-the-trade

If this research has inspired you to invest in gold and silver, consider GoldSilver.com to buy your physical gold:

https://goldsilver.com/?aff=TMB

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.