Beijing's Green Light

After repeatedly teasing the idea of incoming stimulus several times last year, getting investors' hopes up only to scale it back and disappoint, recent memos from State officials give China's stimulus plans a precise framework they are looking to deliver on. Officials indicated they are waiting to launch the long-awaited "stimulus bazooka" once improving Chinese economic data is met with deteriorating US data.

This is a historically unusual combination, as global financial flows tend to move in sync (booms and busts are global). Never before has the US entered into a downturn without China. It suggests that Beijing is waiting for early signs that the Mainland economy has decoupled before deploying roaring stimulus.

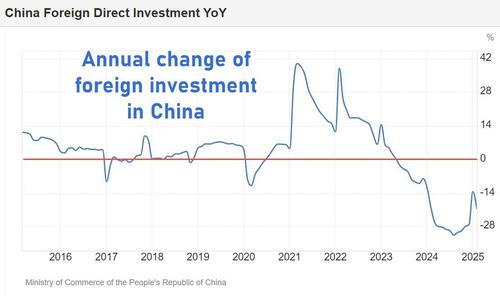

Finance Minister Lan Fuan points to the fact that Chinese strength relative to US weakness would necessarily attract new foreign direct investment (FDI). Positive real GDP and new FDI coupled with massive consumption stimulus is the path China seeks out of the stubborn economic malaise it has faced since Covid.

The Chinese State Council released a better-than-expected Q1 GDP report this week, and US GDP looks to decline in Q1. That's the exact divergence Chinese officials have been waiting for to greenlight massive stimulus.

Chinese stimulus will mean inflation (rising wages, growth and improved employment) and higher bond yields. China's lenders will be in a stronger position and credit spreads will lower. Chinese equities, specifically in sectors whose performance is tied to domestic demand, will also benefit. Demand for industrial commodities - in particular oil, copper and other metals - will increase.

Western officials continue to talk up looming delisting threats and investment bans, but both look to be far off as reciprocal investment bans from China could collapse the private sector and disturb the Treasury market in ways that would make the recent stress look like a walk in the park.

Chinese inflation has been consistently printing low or negative over the last couple years, stuck between 1% and -1%. This may sound attractive to Americans who are currently saddled with a generation of high inflation (absent a very hard, painful and politically untenable landing), but the Chinese business sector has grown anemically, unemployment remains elevated, and evidence of capital flight continues to appear almost every month. China's economy has been bleak since Covid.

This is the only way to make sense of their market for government debt. Consider the 10-year Chinese bond yield, below. The bonds issued by an economy in excellent shape would not be doing this. Instead, bonds (and gold) resemble commercial banks fleeing into cash and safety:

Not a good picture.

The "silver lining" for foreign investors in Chinese equities is that the worst case has been priced: if you bought the Hang Seng, the benchmark index on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, three years ago, you haven't turned any profit. This is the result of an overwhelming wall of bearishness and Wall Street cynicism that's persisted since a few years before Covid. As I tried to emphasize in The Path of Tariff Pain, Western elite, officials, politicians and media truly believe that China will completely fall apart without the US.

Here is an example of what one politically-influential author published last February:

Chinese economic data continued to disappoint last year, as the global South superpower continues to flirt with a depression while rumors of them flooding the economy with stimulus never came to fruition or only did so insufficiently. Foreign direct investment (FDI), money entering China from abroad, collapsed last year and has since only slightly recovered from abysmal levels:

Safe to say that, when all things considered, a complete China bust has already been priced.

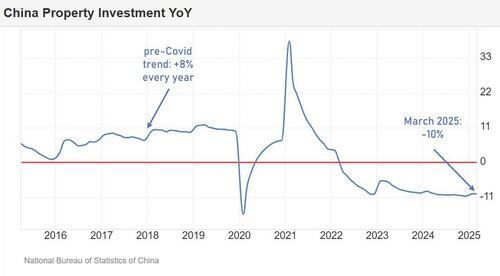

The two main sources of demand for any economy are investment and consumption. There are three areas of investment—property, infrastructure and manufacturing—that the authorities could stimulate, but China has faced problems in each.

A recovery in property investment could be a source of growth, and the Chinese real estate sector famously drove incredible surges in GDP in prior years, but there's little reason to expect it will return. Since the 2021 default and subsequent collapse of Evergrande, Beijing has been reluctant to stimulate mass urbanization projects and incentivize the "ghost cities" that many have compared to a state-sponsored Ponzi scheme, hence why property investment still prints negative:

Similarly, Beijing is increasingly reluctant to rely on infrastructure investment for new growth because they are wary of the sheer extent by which, over the past decade, non-productive & wasteful infrastructure investment (to meet sky-high growth targets) had caused an astronomical surge in local-government debt burdens. If anything, they've indicated a desire to restrain it so local-government debts can be managed.

The authorities bet very heavily on a surge in manufacturing investment to reach their growth target, but seriously underestimated the reaction of the rest of the world to a policy which required that it accommodate a growth strategy in which China's share of global manufacturing (currently 31%) would rise at twice the rate its share of global GDP (17%) and at 3-4 times the rate of its share of global consumption (13%). The rest of the world was never going to accommodate this output.

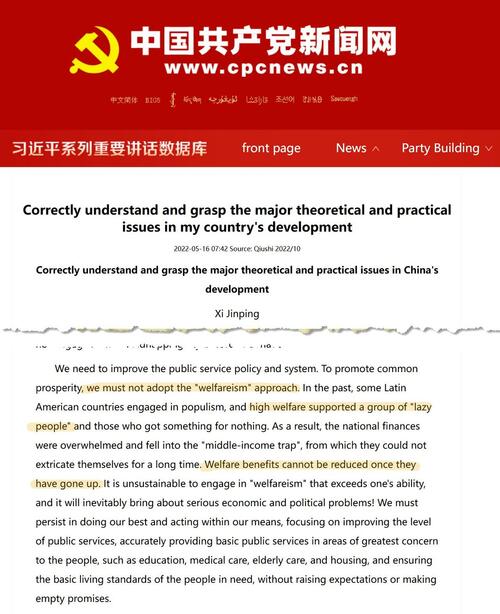

Assuming that an sudden surge in household confidence (which collapsed in early 2022) is unlikely, all that's left is to stimulate consumption. This is what China bulls have been waiting for. Many analysts have insisted for years that this would never happen because of Xi's opposition to "welfarism", the idea being that support for the household sector will cause Chinese workers to become "lazy" like happened in "some Latin American countries."

However, China's Third Plenum, held last July, and other more recent speeches from Xi and Beijing officials indicate that government officials have made a pivot on the idea. The latest budget report from the Ministry of Finance, delivered to the National People's Congress in March, clearly emphasizes a focus on servicing the wellbeing of consumers. Beijing now realizes their options are not welfarism versus no welfarism, but rather between welfarism, a disruptive surge in debt, and missing their growth target altogether. Faced with it being their only option to meet (and exceed) growth targets, they are now willing to subsidize household spending.

The only question is "what are they waiting for?"

China, as a political institution, is opaque and it's not always clear where their policy influence comes from. The state keeps a lock on media for the most part, and official government portals only release formal policy documents, press releases, and official statements after they are carefully curated for the public. Unlike the US where policy is more like an open book due to politics, culture and media, China keeps their short-term policy intentions nebulous (hence all the speculation about and "rumors" of stimulus).

Financial authorities in China adopt and espouse what's called the Beijing Consensus (a.k.a. the China model) - a framework that prioritizes independence from foreign influence and Western-style democratic reforms while seeking to reduce inequality and balance growth across regions. Like any country, China has growth targets they strive to hit, but, for Beijing, growth should not come at the cost of economic distortions that have plagued the West. This is in contrast with the so-called Washington Consensus, which is increasingly reliant on Modern Monetary Theory logic — the belief that deficits don’t matter in a reserve currency regime, and that governments can spend their way out of downturns - and hinges on a unipolar world order.

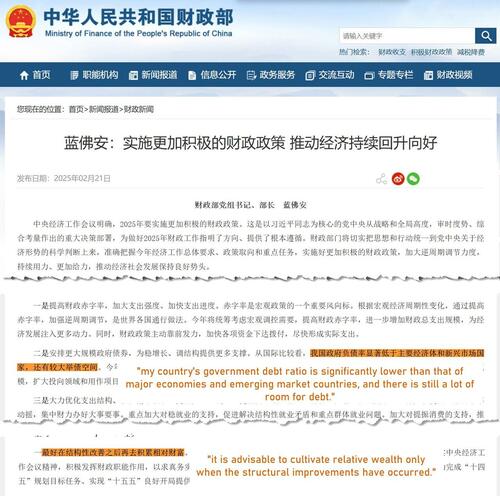

Where the China perspective differs is that it deems fiscal stimulus only effective in support of ongoing structural improvements and real growth, rather than being deployed to re-inflate nominal growth in an immediate response to weakness. This is a total repudiation of MMT which says running enormous fiscal deficits is an effective way to grow out of an economic slump: the bigger the downturn, the bigger the deficit. Top Chinese economists, including Liu Shijin who holds influence over Finance Ministry officials, underscore that stimulus is only effective with structural reform, otherwise it fosters inequality and other inefficiencies, as has been observed in the West.

China even has a phrase for this: the British disease.

Crucially, "structural reform" and "structural improvement" refer to changes in the geopolitical landscape as much as they do changes to domestic policy. The two are used interchangeably depending on context. So if the Ministry of Finance discusses "structural improvement" while the embassy describes "geopolitical improvement", both will appear the same when translated into English from Mandarin.

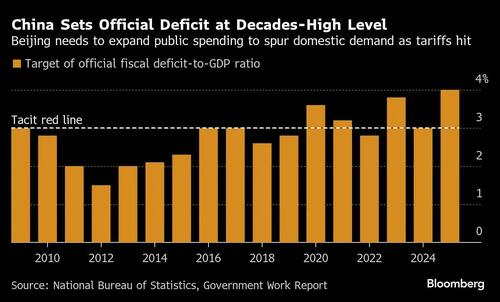

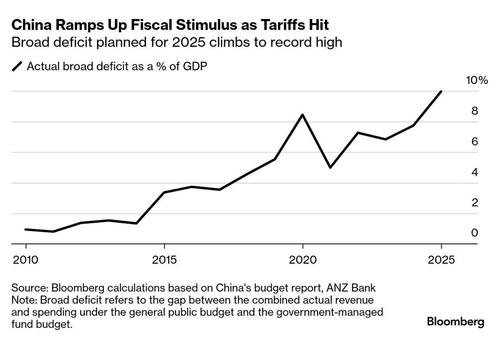

Beijing's Ministry of Finance outlined last month an expected 2025 deficit of ¥5.66 trillion, or 4% GDP (up from 3% last year), which according to Bloomberg is the highest in 30 years.

The Ministry of Finance made the unusual (and notably unprecedented) decision to refer to China's fiscal deficit as a tool "that inhales and exhales", signaling they are ready to expand it depending on how data responds. Bloomberg also notes that the actual broad deficit, which accounts for local government deficits, signals the fiscal pulse will be stronger-than-ever this year:

A state letter issued last week by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), who is involved in approving major investment projects & stimulus plans, confirms Chinese officials realize that stimulating the services industry is the key to reviving the economy. This has long been acknowledged and is certainly not unique to China, but what investors have tried (and repeatedly failed) to time is the question of when.

In a February memo, top Finance Minister Lan Fuan, who is privately known as a geopolitical hawk and oversaw (very likely coordinated) commercial banks buying gold last year (to then sell to the PBOC), went so far as to outline the exact case in which China could emerge "from the hibernation" and grow unfettered. His idea, which we can assume is the working framework of the Party, indicates that "it is better to cultivate relative wealth when the structural improvements have occurred."

Here, Lan echoes the Beijing Consensus - instead of jamming stimulus into stagnation, he advises nurturing the economy when the geopolitical playing field has changed to China's advantage. Based on his use of the same phrase in prior dialogues, by "the structural improvements", the Finance Minister is specifically talking about when US growth is prepared to decline (as Chinese growth rises).

In other words, "it's better to stimulate when my country is growing and when my competitors' country is shrinking."

Finance Minister Lan also indicates that the duality of strong Chinese growth with declining US growth would necessarily attract new foreign direct investment. For international investors, all else equal, this makes total sense. Quite literally a matter of "do you want your capital to appreciate over the next decade, or not?"

Acknowledging that he is unconcerned about debt and is willing to increase it suggests exactly what it sounds like: unlike the US, whose fiscal space is already limited because of growing deficits, China sees abundant room for stimulus. Importantly, this is new language, as China had telegraphed concerns over local government debt burdens for a long time.

That means this week's GDP beat signals what Chinese authorities have been waiting for. Whereas pundits at Bloomberg seem to think the strong data from Q1 limits their room for any stimulus, that is a US-centric frame. It's the strong data that sets the stage for stimulus.

We'll only know for certain on April 30th when real GDP from the US in Q1 is released, but the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow forecasts the first decline in three years. Even when adjusting for the outsized gold imports, real GDP is, at best, flatlined:

Indeed, some of the relative difference in real GDP between China versus the US is a result of export pull forwards, and growth in China's export sector is set to slow for obvious reasons. What better time to stimulate household consumption than when US demand is about to slow? China is looking to integrate these firms, who relied on exports, into the domestic market, at a time when households will have more disposable income ready to spend. Perhaps it won't make up for tariffs completely, but it will certainly ease the headwind and fill the gap left open by US consumers stepping away.

Stimulus - whether that's tax cuts or fiscal spending - means issuing more debt. Like in every other market on earth, one of the basic factors that drive bond prices (and yields) is supply & demand: when there's so much issuance such that commercial banks, the private economy and foreign investors have trouble digesting it all, prices fall (yields rise). In the US it's slightly different, but this is a simple and accurate way of thinking about it.

With a new supply of bonds and deficits, Chinese yields will rise. For Americans, it's hard to think about how this could possibly be a good thing.

One of the distinctions between higher US yields versus higher Chinese yields is that when the former rises, it tends to be a volatile swing. This is not a call for Chinese yields to spike to 8%, but to rise from the 10-year depression that is currently being priced.

Higher-yielding Chinese Government Bonds could also directly attract foreign fixed-income investment, who chase higher yields abroad when domestic yields are low. Although it's unlikely we'll see a global rotation, east Asian fixed-income investors like Japan have already signaled an intent to step away from Treasuries. Japan has historically been the chief foreign marginal buyer, but, with no end in sight for US bond supply, they will necessarily repatriate capital. If Chinese yields begin to rise to the 3-handle or above, there is real potential for foreign investors to begin financing Chinese deficits.

Not only that, but a lack of reinvestment into US Treasuries from foreign official accounts are still likely to accelerate as the decoupling continues. Earlier this month it was enough to not only send yields racing higher but also widen the cash-futures basis such that basis traders faced margin calls on their long basis positions. Going forward it may be more orderly, or it may not be. There is obviously a political element to this that's difficult to predict, but expect a disorganized deleveraging in US Treasuries to follow any political and/or liquidity hiccup. I've said it would come on the heels of this year's tax season but, if it doesn't, watching the trade war is our best guess.

~

Much of the deflation in raw commodities the world has enjoyed since Covid, at least before they're sold to distributors who inevitably raise prices to meet margins, is a manifestation of the Chinese slump. A stronger economy and more aggregate demand from China would necessarily increase demand for commodities. In particular, the "unloved" industrial metals like copper and palladium.

Some sectors will see a stronger tailwind from all this than others. Chinese banks, consumer discretionary and consumer staples will especially benefit. Below are a list of H-shares (Chinese stocks that trade on the Hong Kong exchange) for companies that would benefit directly. Many popular and reputable US brokers, like Interactive Brokers and Charles Schwab, allow for trading H-shares.

I would strongly advise Americans against getting exposure to China via A-shares (Chinese stocks that trade in Shanghai). Fewer reputable US brokers include trading services on A-shares. Not only is it harder to do so anyway, but there are slippage and broker-related headaches that I've personally ran into before. Fortunately, there are plenty of companies that trade through Hong Kong.

Chinese Banks

The Chinese yield curve remains flat or inverted, where short-term & deposit rates are equal to or slightly above longer-term bond yields. This has throttled Chinese banks' net interest margins (NIMs) because, like just about every bank, they "borrow at the short end and lend at the long end." NIMs measure a bank's profitability by showing the difference between interest income earned on assets (like loans) and the interest expense paid on liabilities (like deposits), so a steeper yield curve due to higher bond yields will improve banks' NIMs.

This is probably best done via the H-shares of large, international, "too-big-to-fail" Chinese banks:

- Bank of China (HKEX: 3988)

- ICBC (HKEX: 1398)

- Chinese Construction Bank (HKEX: 939)

- Agricultural Bank of China (HKEX: 1288)

Alternatively, if you have the margin and want to reduce risk in the event a banking problem goes global, you could set up a Long/Short position that's long Chinese banks and short US banks.

Chinese Consumer Discretionary

Chinese sectors that rely on international exports (like apparel, furniture, toys, personal care & cosmetics) would see the loss in export growth blunted by domestic growth via consumer stimulus. Some ideas include:

- Anta Sports (HKEX: 2020) - leading apparel and footwear company.

- Li Ning Company (HKEX: 2331) - major sportswear brand.

- JD Inc. (HKEX: 9618) - preeminent e-commerce platform.

- China Mengniu Dairy Company (HKEX: 2319) - One of China's largest dairy producers.

- Nongfu Spring (HKEX: 9633) - top beverage company.

- WH Group (HKEX: 288) - world's largest pork company.

- Pop Mart International (HKEX: 9992) - leads in domestic entertainment products & toys.

- Haidilao International (HKEX: 6862) - the most popular 'hot pot' restaurant chain.

- Goodbaby International (HKEX: 1086) - leading manufacturer of baby products.

These companies are well-positioned to benefit from a boost in domestic consumption in mainland China.

Chinese Consumer Staples

The consumer staples sector would also benefit from boosted domestic consumption. Some idea include:

- China Mengniu Dairy Company (HKEX: 2319) - One of China's largest dairy producers.

- Yili International (HKEX: 1117) - Largest dairy producer in Asia.

- Nongfu Spring (HKEX: 9633) - top beverage company.

- Tingyi Holding Corp. (HKEX: 322) - Known for Master Kong instant noodles and beverages.

- Want Want China Holdings (HKEX: 151) - Specializes in rice crackers, dairy products, and snacks—household brand.

- Dali Foods Group (HKEX: 3799) - Wide range of packaged foods and beverages, especially in Tier 2/3 cities.

- Uni-President China Holdings (HKEX: 220) - Taiwanese conglomerate with strong mainland China food/beverage footprint.

- WH Group (HKEX: 288) - world's largest pork company.

- China Resources Beer (HKEX: 291) - Market leader in beer; owns most popular brands.

- Yonghui Superstores (HKEX: 9868) - China's largest grocery retailer.

Alternatively, most brokers do trade Chinese ADRs (Chinese stocks that trade on US stock exchanges). For example, here are popular Chinese ETFs:

- KraneShares CSI China Internet ETF (NYSE: KWEB)

- iShares MSCI China ETF (NYSE: MCHI)

- iShares China Large-Cap ETF (NYSE: FXI)

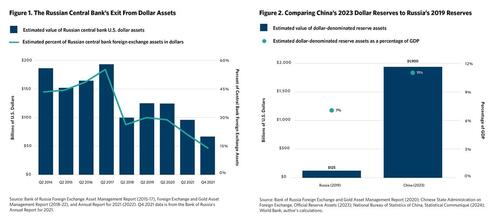

The obvious obstacle would be in the event of US executive actions that "delist" Chinese ADRs and/or, more harshly, totally ban cross-border investment in China (which includes H-shares). This happened to Russia in February 2022, and Treasury secretary Bessent has indicated all options are "on the table." Note that fears over delisting Chinese ADRs is exactly what happened in 2022, and it's probably true that the US likes to float the idea so as to make investors second-guess deploying capital into China. That's especially true if Chinese assets start to outperform American assets, which hasn't been the case in years.

Of the two concerns, a total ban on all cross-border investment is unlikely because China would reciprocate. The most recent TIC data reports mainland China holds about $359 billion in US equities and over twice that in Treasuries. The TIC data also suggests that China is a marginal investor in corporate debt via accounts in Belgium and Luxembourg. The market for US corporate bonds is far less liquid than that for Treasuries, so pulling away any foreign marginal investor could wreak havoc.

Formally delisting Chinese ADRs, only slightly more likely, would probably be also met with reciprocity. This is not comparable to 2022's delisting of Russian ADRs such as Gazprom, because Russian investments in the US had already been small and declining since 2014, while US investments in Russia (Russian ADRs or equities traded in Moscow) were absolutely tiny.

I would also note however that in 2022, the US and allies overestimated the damage financial sanctions against Russia would have and underestimated how resilient the Russian economy would be.

In any case, betting against China today would be tantamount to a bet that they will completely fall apart. I wouldn't expect it.