Come Hell or High Water: Here's the Real Reason to Expect Deep Rate Cuts

The Fed will resume rate cuts much more aggressively than anyone expects by the summer, and rate hikes are completely off the table for the foreseeable future.

Rate cuts are the most effective way of improving Treasury market liquidity without resorting to open market operations like QE, or deregulation, because they open a liquidity spigot by reducing the cost of hedge funds' Treasury trades. Put one way, "rate cuts lower the cost of Treasuries" by making them less expensive for hedge fund buyers.

It seems the Fed is only willing to go for more rate cuts in the event of an "unexpected" economic downturn, in particular a spike in unemployment which, as I described last month and as plenty of people have said at this point, is probably on its way. Although to cut by something even close to what they may need, any downturn would have to be an undeniable recession, forcing the Fed - which thinks current policy is "significantly restrictive" - to embark on an official easing cycle.

Something big has been brewing under the hood over the last four months, and it's been given zero attention in financial media. From my personal interactions, most so-called financial professionals and "macro experts" don't have a way of explaining it. Only those who are directly involved have the most credible theory.

First, some context.

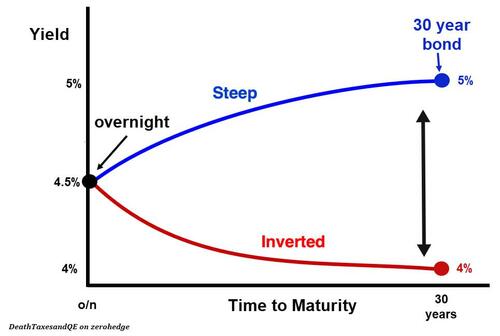

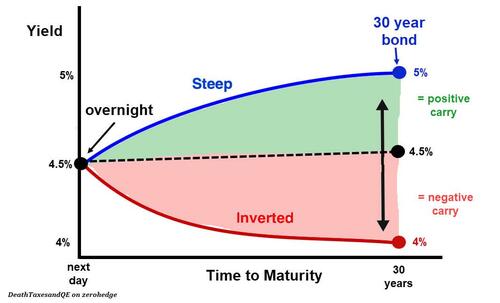

In my November article, I said that a steep yield curve - one where longer term Treasury yields are above shorter term yields and overnight rates - should invite price sensitive market participants such as banks, real money investors such as life insurers, and FX-hedged foreign buyers like the GPIF to buy Treasuries from dealers. By "price sensitive", I mean investors who buy Treasuries to collect interest.

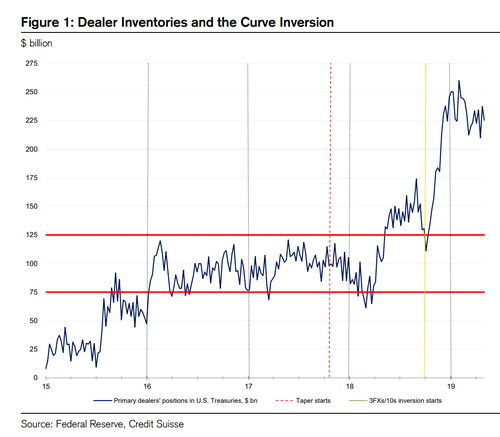

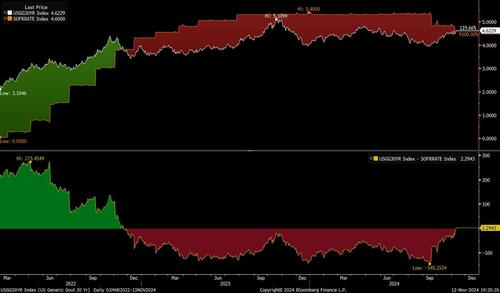

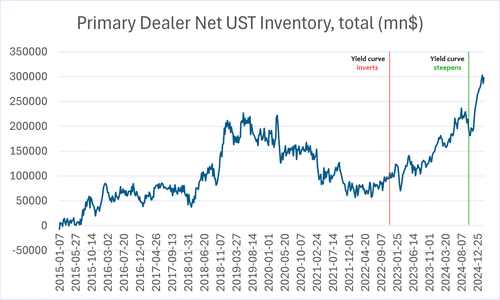

The yield curve inverted in late 2022 and, while it remained inverted for the next two years, dealers had been steadily amassing Treasury inventory since. Though they can hold a lot of assets on their balance sheet, particularly without much volatility, there are regulatory limits that officials are not ready to change without a serious market accident.

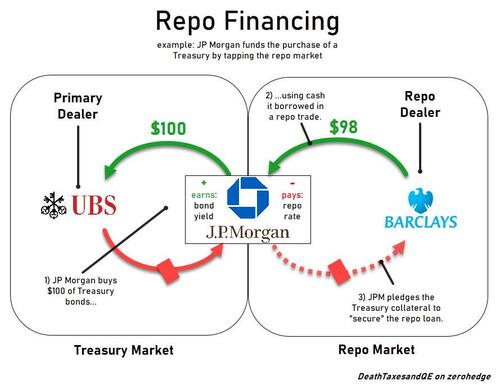

The reason "where overnight rates currently are" is so important is because, while Treasuries can of course be purchased outright, many are financed in markets like repo, where, after buying a Treasury, the buyer goes to the repo market and pledges the Treasury he just bought as collateral for a cash loan. The cash received from the repo loan is used to settle the original Treasury purchase on the next business day (called "T+1 settlement").

This is a confusing way to think about it, but is how trillions of dollars in securities, including Treasuries, are funded every day. Dealers fund their Treasuries with overnight (o/n) repos, maturing the next day. Hedge funds, banks and others mostly fund their Treasuries with term repos, maturing at a specific date in the future. Overnight and term rates are similar, and it's these financing rates that are effectively the cost of the Treasury for said investors.

In the simplified example below, the ultimate buyer is J.P. Morgan, who goes to the repo market to fund most of the Treasury he purchased from UBS for $100:

Consider again the inverted yield curve. It wouldn't make sense for a bank, for example, to finance a 30 year bond in the repo market if he's paying a 4.5% repo rate and collecting a 4% coupon (i.e., interest). He's paying more to keep the trade alive than he's earning on the trade itself - that's negative carry, and a result of an inverted curve. Since FX-hedging costs are closely tied to overnight rates, it wouldn't make sense for foreign buyers such as the Japanese, who usually have a robust appetite for US bonds, to do so either.

Here's Zoltan Pozsar describing exactly this in his May 2019 note, "Collateral Supply and o/n Rates":

"Ultimate buyers don’t always buy. Banks and non-banks are price sensitive buyers – they only buy if it makes sense to buy. The yield curve determines if it makes sense to buy Treasuries, and, if the answer is no, primary dealers still have to, because hell or high water, the Primary Dealers Act of 1988 requires them to...

"Since the fourth quarter of (2018), it made no sense to buy Treasuries because the yield curve inverted relative to all the relevant funding costs that matter – repo and FX hedging costs – and so ultimate buyers didn’t gorge on Treasuries. But primary dealers had to, and as they did, their inventories swelled..."

"When the curve inverts and dealers buy, they fund with o/n repos because they are in the moving business, not the carry business.

"Dealers buy because they have to, not because they want to, and hedge funds buy because they think the Fed will soon cut rates. It's these funding needs that pressure o/n rates, and if rate cuts do not materialize, pressures can ricochet to the long-end of the curve."

Fast forward to just a few months ago when the Fed ended the year with four hawkish rate cuts - lowering rates and prompting a bond selloff (higher yields). When the Fed raises or lowers interest rates, they're doing so by toggling a range within which all overnight repo and reverse repo rates - the cost of borrowing and lending dollars overnight, respectively - are supposed to trade.

The lower rates and higher yields steepened the curve relative to all the relevant funding costs that matter and allowed for, as Zoltan would say, price sensitive buyers who finance their Treasuries in repo to earn a positive carry. The steeper curve gives banks and non-banks, domestic and foreign, the greenlight to buy Treasuries from dealers. In doing so, their buying removes much of the regulatory burden said dealers were facing.

That was several months ago, and, by now, you'd expect investors to buy Treasuries from dealers because, since then, in most cases, it made sense to buy Treasuries...

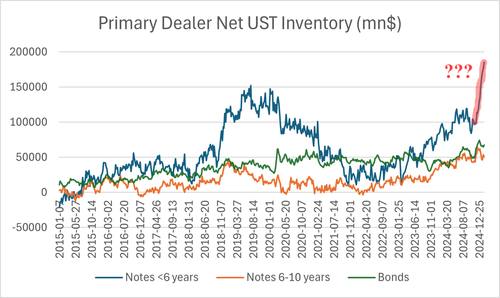

... At least this is what should happen, but, when taking a closer look at the data, the opposite appears to have actually happened. Dealers faced a surge in inventory just as everyone expected relief!

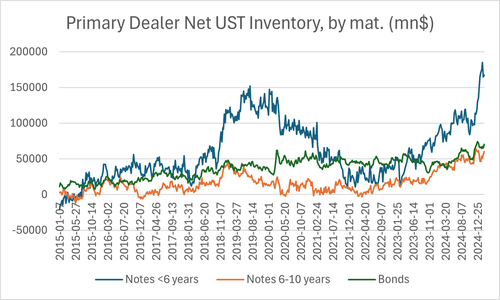

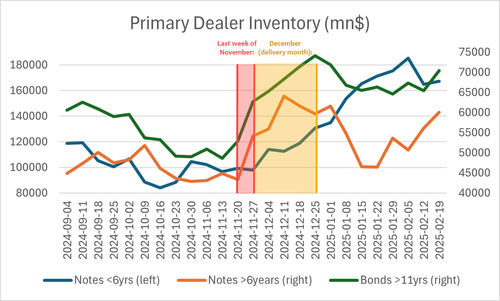

The statistics from the New York Fed further break down this inventory by time to maturity. Clearly, the total uptick is mostly in Treasury notes that have less than 6 years to maturity (blue), but there was also a sizeable upswing in bonds with more than 11 years to maturity (green):

The uptick really makes no sense, and there's shortage of theories that tried to make sense of it. Everybody has their own version of events, but looking at the primary dealer data more closely, we can quickly rule out two things: 1) it wasn't in response to the Fed's rate cuts, and 2) it wasn't a reaction to Trump. Both events were widely anticipated, so the idea that investors waited until the last week of November before suddenly puking $100 billion of illiquid Treasuries doesn't hold water.

The most credible theory looks beneath the surface and into what in August I said was the most important trade on Earth - because for now, and especially now, that's what it is: the cash-futures basis trade (the basis trade).

btw this is where the next really big crash will start https://t.co/XcK2RezYEk

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 1, 2024

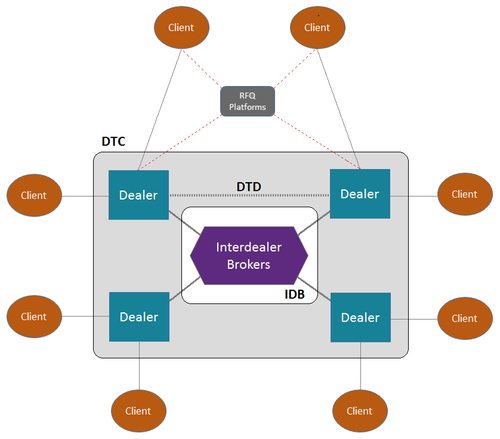

The basis trade is a relative value (RV) strategy mostly taken on by hedge funds, and continues to provide liquidity in the all-important cash Treasury market. "Cash Treasuries" are the actual notes & bonds that were auctioned by the Treasury, some last month and others 29 years ago, and pay a coupon twice-per-year until they mature, and the cash Treasury market (also called the "secondary Treasury market") is where investors go to buy them from and sell them to "bank dealers."

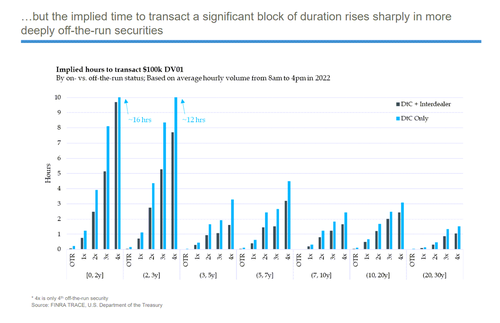

The trade has given hedge funds the role of the marginal buyer of cash Treasuries, which is especially critical so long as the Fed continues to sell its own portfolio of cash Treasuries in QT. The securities sold to non-banks by the Fed in QT are not the ultra-liquid, most recently auctioned on-the-run (OTR) Treasuries, but are the illiquid off-the-run (OFR) Treasuries, some issued over a decade ago. Fortunately for the Fed's plan, basis trades absorb off-the-runs.

Basis trades seek to profit from the relative value between the Treasury's cash price and the price of the corresponding Treasury futures, which is a contract that obligates the buyer (or seller) to take (or make) delivery of a specific Treasury at a predetermined price during the delivery month. Most other futures don't involve physical delivery, and instead are cash-settled. But for Treasury futures, there is no option for a cash settlement - futures shorts must deliver a bond at maturity. It's the prospect of having to make or take delivery of an actual Treasury that helps price the futures.

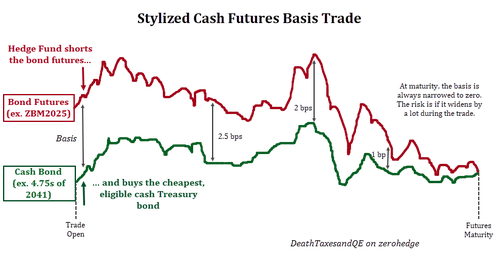

For a few reasons, there's normally a tiny price discrepancy (called the basis) where the futures price trades slightly above the cash price. To take advantage of this basis, since the cash is cheap relative to the futures, hedge funds will buy the cash Treasury and short the Treasury futures.

Few things are certain in markets, but the futures price will always converge with the cash price the moment before the futures contract matures. That does not mean the basis trade is a risk-free arbitrage. There are at least two well-known risks, one is a risk to the hedge fund and the other is a risk to the system.

To make a tiny basis worthwhile for a hedge fund, he will need to access leverage from his repo dealer, which often means posting only $2 of his own capital and borrowing another $98 to buy $100 in Treasuries. Keep in mind that these 2% haircuts ($2 is 2% of $100) are standard for the top RV funds, and haircuts can be even less or, in some special cases, zero.

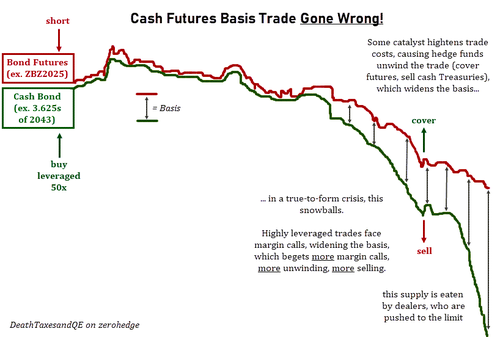

As with any relative value trade, the risk for him is for the basis to suddenly widen, as happens in a violent market dislocation like Covid, because he is required to pay variation margin on his futures short. Normally, changes in the value of the Treasury will offset the variation payment, but if it doesn't, the basis trader may face a margin call, forcing him to make a sudden cash outlay and unwind the position.

This is the vicious cycle that spiraled out of control during March 2020.

It's hard to describe just how destructive this can be, because the Treasuries the hedge fund bought using 50x leverage and is now fire-selling due to margin calls were already very illiquid (and difficult to sell as they were).

OTRs are much more liquid than even 1st off-the-runs. You can imagine how difficult is would be for a hedge fund to find a buyer for deeply off-the-run Treasuries. (source)

A different risk is for the trade to have no measurable profit potential. That's not as much a risk for the basis trader himself, who would simply not enter the trade to begin with, but could be one for the financial system, because it would leave the Treasury market with one less class of buyers and even less liquidity. If hedge funds had not stepped in as significant marginal buyers over the last two years, volatility would've quickly ensued such that reducing the size of the Fed's balance sheet would be impossible.

This is what appears to developing right now...

FED'S POWELL: I'VE BEEN SOMEWHAT CONCERNED ABOUT TREASURY LIQUIDITY.

— FinancialJuice (@financialjuice) February 12, 2025

Think back to what I mentioned earlier - investors obviously won't enter into a trade if it's expected to incur negative carry: when the cost of the trade exceeds the yield of said trade. For ultimate Treasury buyers, like banks, who repo finance the purchase of 20 year bonds, for example, their cost is the repo rate (ex. about 4.35% as of today) and their yield is the accrued interest from the security (4.60% as of today). That would be 25 basis points of positive carry - profitable.

For the basis trade, it's not that simple. You would think it should be easy to figure - if the trader makes more on the basis than he pays to repo finance the trade, he has a profit and positive carry, right? Yes, that's true, but it misses the bigger picture.

There's not a single basis, but a range of bases. There are eight different futures contracts the hedge fund can short, from 2-year T-Note futures to Ultra T-Bond futures, each one having four distinct maturity dates in March, June, September and December. That totals 32 different futures contracts from this year to short:

On the other side of a basis trade is buying the cash Treasury. When basis traders are short Treasury futures, they're agreeing to deliver a cash Treasury during the delivery month (March, June, September or December) to the futures buyer at the futures' price. But they can't just deliver any security - each futures contract has a designated basket of cash Treasuries that are eligible to be delivered. Only bonds that, in June, have 15 to 25 years to maturity remaining can be delivered onto the June 2025 T-bond futures contract, for example. There are currently 58 deliverables (eligible bonds) on that contract.

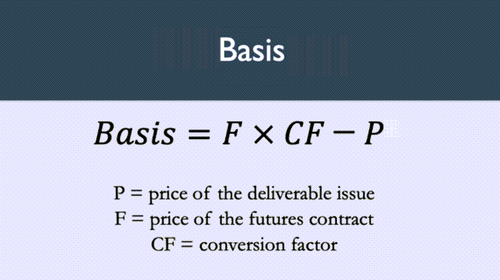

It should be clear that profit margins on the trade, even when accounting for leverage, are razor thin, so every penny and every basis point counts. Hedge funds can buy at least several (and sometimes dozens) of bonds that are eligible to be delivered, but generally one or two will price out to be most cost-efficient to deliver. This bond, that's both eligible and most cost-efficient, is considered the cheapest-to-deliver (the CTD).

Since there's only a single futures, we're just looking for the Treasury with the highest invoice price, which is what the long position pays us when we deliver on the futures. It includes a conversion factor, which adjusts for coupon differences among eligible bonds, to ensure fair pricing by aligning the CTD bond’s market value with the futures contract, effectively reflecting the cost to settle the trade.

The best way to put it all together is by walking through an example.

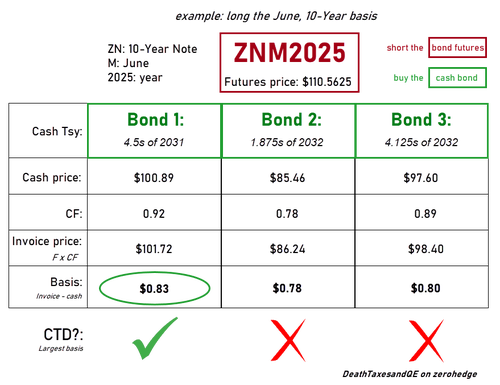

Let's say we're an RV fund and looking to "go long the June, 10-Year basis." That means we see a basis between June futures and 10-Year cash Notes that we think is worth trading. First, we'd short the June 2025 10-Year futures. That part is straightforward. Today, the futures is trading at 110'180 (which is bond lingo for 110-18/32, or $110.5625).

By shorting June 2025 10-Year futures, we're agreeing to deliver an eligible Treasury which has, in June, between 6.5 and 8 years remaining before maturity. Imagine there are three deliverables - Bond 1, Bond 2 and Bond 3. To complete the trade, we must decide which is the cheapest-to-deliver, because the CTD is the one we'll buy.

If the CTD means the cash Treasury with the largest basis, then we'd buy Bond 1:

But, while the CME and all these pedantic formulas may tell us which Treasury is the cheapest to deliver of the eligible basket, what it doesn't tell us is just how profitable, or if it is at all. The basis is almost always positive, but that doesn't necessarily mean a hedge fund can turn a profit on it, because it ignores the costs of the trade. Remember, our cost is the repo rate we pay to finance the Treasury.

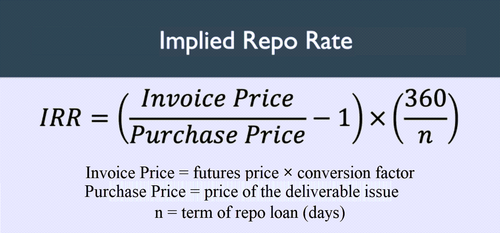

The implied repo rate (IRR) is the profitability of basis trades: when the IRR is greater than the actual repo rate, it's profitable to buy the cash Treasury and short the corresponding Treasury futures, while borrowing in the repo market. At delivery, the trader will earn the spread between the IRR and the repo rate. Those long-basis trades are the ones that buy Treasuries and keep the world spinning.

The formula below is simpler than it looks. All it means is that a bigger basis is more profitable, and shorter-dated basis trades are all else equal more profitable than longer-dated ones.

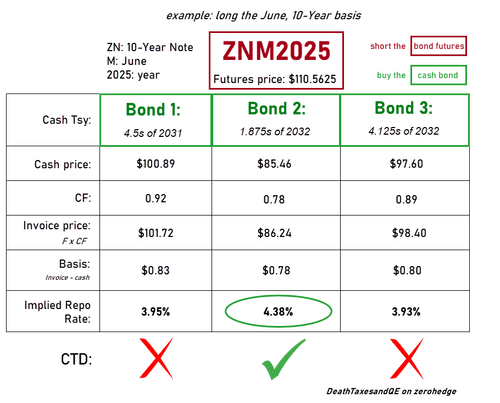

Since just about every basis trade involves borrowing in repo, a better way for hedge funds to find the CTD is by looking for the highest IRR. Go back to the example from just before, where we are looking for the CTD on June 10-Year Note futures. The CTD is the Treasury that hedge funds will buy because they think they can turn the greatest profit on it, but, if they don't think they can profit, they won't buy.

The CME calculates implied repo rates for free, so there's no need to do all of this work by hand. Needless to say, there's normally a cushion of space, where implied rates on various contracts trade above repo rates. In other words, long-basis trades are normally profitable because implied rates normally trade above actual rates.

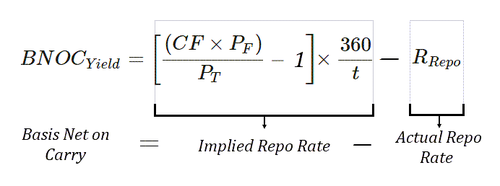

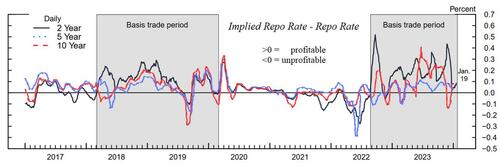

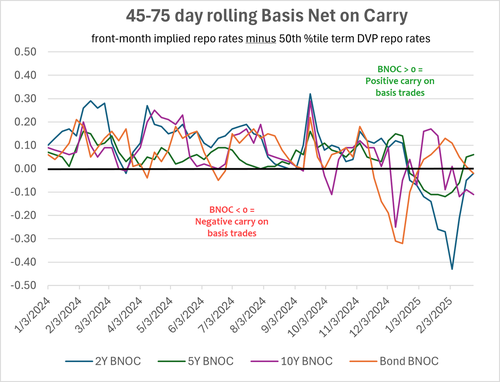

Last March, the Fed studied the basis trade and measured this exact phenomenon: implied repo rates minus actual repo rates. The authors called this the "basis net on carry" (BNOC), which is essentially the trade's profit:

Notice how the trade can be profitable on one basis, but not profitable on another. Also notice how when the carry does turn negative, and the trade unprofitable, it's normally for a brief time and an insignificant amount:

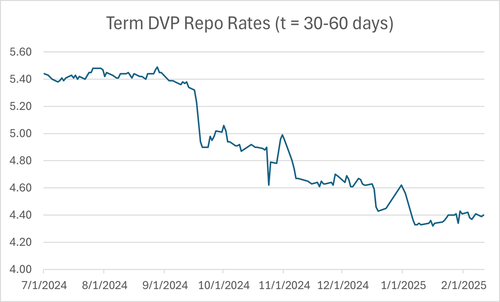

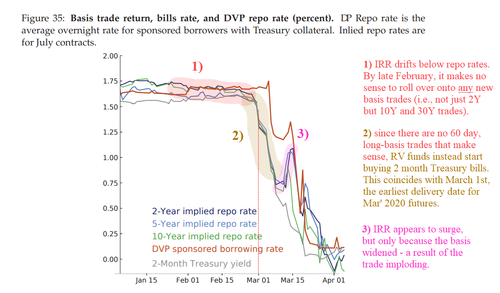

For reference, below is the average term repo rate in the DVP venue, which is the average term rate that hedge funds will pay to finance their Treasuries. This is the cost of the Treasury - does it make sense to buy?...

... it makes sense for basis traders to buy when implied rates are above actual rates. That's a positive basis net on carry. But when the actual repo rate is greater than the implied rate, it's no longer profitable to buy the cash Treasury and short the futures, and so, hedge funds will not buy. They will not enter into new basis trades if it doesn't make sense to, and, when their demand evaporates, dealers get left with a bigger burden. Worse, in some cases, they can do the opposite: go short the basis by shorting a cash Treasury and buying the corresponding Treasury futures, while borrowing in the repo market. Though in my conversations with RV traders, shorting Treasuries is less practiced, even when it's a profitable approach.

And whaddya know...

The implied repo rate data in the chart above is grainy - it's taken by hand from several days (the ones that had the highest Treasury futures volumes) per week, and then smoothed. Cash and futures prices are changing all day long, so individual data points during the day should be averaged down. The IRR can print something unrealistic, like 26%, but this just indicates the futures is illiquid. What's more important is the trend, and that BNOC turning negative perfectly coincides with rises in dealers inventory for those same Treasuries.

If you've been following along, then, hopefully, this chart I shared earlier makes some more sense:

This article is already getting technical, and long, so exploring the "why did this happen" question, while important, is for now beyond the scope of what I wanted to describe. In concise terms, a surge in term premia disproportionately cheapens longer-duration bonds, while the CTD (often the shortest deliverable) remains relatively expensive due to its lower duration. This mispricing narrows the basis, making the trade less attractive.

In February 2020, indeed before the word "coronavirus" entered into mainstream consciousness for most people, implied repo rates drifted below actual repo rates, signaling that entering into new basis trades was no longer profitable. Because it was not profitable, hedge funds did not buy. They delivered on their March basis trades at the earliest possible date (March 1st 2020) and, instead of rolling onto new, June basis trades, which would not be profitable, they piled into 2-month Treasury bills. Hedge funds decided that since they could make more on a 2-month bill than a 2-month basis trade, that's what they'd do.

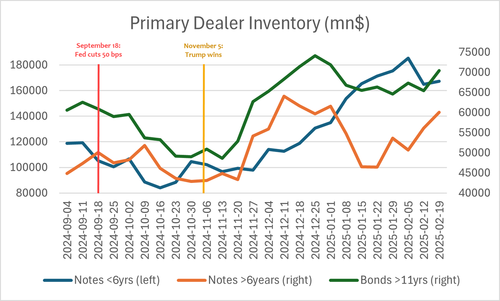

There were obviously other things going on in 2020 that make comparisons difficult, but don't be surprised if 2-month bills begin to price several rate cuts on June 1st this year, just like they did on March 1st 2020. The issue would most likely arise during a delivery month (like March, June or September), and the last week of the month before (the last week of February, May or August) would see dealer inventory spike...

...unless the Fed cuts repo rates.

Dealer inventory reporting from the NY Fed lags by two weeks, but we're already starting to see this occur again, just like it did in November/December. Bonds (in green, below) are by far the most burdensome for dealers to warehouse, so that's the figure we should pay attention to:

Officials do have a few options before cutting repo rates, but none are better.

What if the Fed ends QT? That would relieve some of these pressures and definitely help. What it wouldn't address is the underlying dynamic: without rate cuts, the illiquid, off-the-run corners of the Treasury market will lose a critical buyer.

What if the Fed lets the U.S. walk into a recession? Investors would probably buy Treasuries - that helps, right? What we're asking is whether flight-to-safety buying would replace the role of hedge funds. Aside from the fact that a recession would warrant rate cuts anyway, the problem with this is that, in a flight-to-safety, investors prefer liquidity. They want to park their money as quickly and as efficiently as possible, and so will buy the most liquid Treasury they can. That would be a recently-issued on-the-run Treasury.

But basis trades provide demand for illiquid off-the-run Treasuries, and pulling those hedge fund buyers away would still create liquidity problems:

What about deregulation? What if they just arm the banks with bottomless balance sheets by doing something like exempting Treasuries from leverage ratio calculations? That would give dealers no limits on the amount of Treasuries they can hold, so all those charts I showed of soaring inventory would basically be irrelevant. It's a solution that months ago I predicted would be used as a line of defense, and only recently is becoming a part of mainstream discussion.

Removing Treasuries from the SLR is Going Big, and there are huge problems with Going Big, especially if it's not called for.

The inflationary impact of bank-QE, a term I coined myself where banks have no limits on their Treasury inventory, is much more aggressive than the inflationary impact of real-QE, where the Fed buys, and rate cuts, in my opinion. In QE, reserves, that the Fed prints in a few keystrokes, are swapped for Treasuries, which the Fed includes onto its portfolio. QE is more of an asset swap, and doesn't inherently create new money. In the modern economy, commercial banks create deposits out of thin air by purchasing assets. That could mean making a loan, which is an asset, or purchasing a Treasury. Their ability to do this is constrained by regulations like leverage ratios, so you can imagine what lifting those regulations would do.

Not only that, but, since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, regulators are very reluctant to encourage banks and their dealers to hold lots of longer-dated Treasury bonds. SVB failed because its exposure to interest rate risk, also known as duration risk, was grossly mismanaged.

This is Powell's last year. Not the time you'd expect him to even consider launching an inflation monsoon. He would rather see Trump tank markets and face the blame for re-inflation, instead of completely soiling whatever shred of credibility he thinks the Fed has left. That degree of deregulation is truly a last ditch option, but, even so, in a genuine panic, I would expect nothing less than for the Fed to shoot first and ask questions later.

Since I began writing this in mid-February, rate cuts have more-or-less become a consensus as the coming growth slowdown grows more and more mainstream...

rate cut odds pic.twitter.com/eUOjJrsluV

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 25, 2025

Although personally, I wonder if this will turn into a chicken-or-the-egg problem, where people think "ah, rate cuts are coming because the economy is slowing and stock prices are down" when, in reality, rate cuts were coming regardless, because, come hell or high water, the Treasury market demands it.